The idea of the "Ten Essentials" has been around a while, dating back to the mid 1970s and promoted by many outdoor education organizations and publications. However, as cavers, we have a different perspective on these needs, which were clearly written with surface expeditions and mountaineering in mind. There are a few variations which have been published over the years, but generally the classic list of the Ten Essentials looks something like the following [1, all citations in this article will be in brackets and references included at the bottom of the page]:

- Navigation

- Headlamp

- Sun Protection

- First Aid

- Knife

- Fire

- Shelter

- Extra Food

- Extra Water

- Extra Clothes

This gives us a great starting point for caving but needs some changes to be more useful underground. Let’s assume the following:

- You are packing for a caving trip in the TAG (Tennessee-Alabama-Georgia) region. Other regions and climates may dictate other loadouts.

- You already are wearing appropriate clothing and footwear for caving, plus a helmet and gloves.

- You are not intending to have an overnight trip.

With those caveats, we recommend the following modified list of Ten Caving Essentials:

- Backup Light/Batteries

- Thermal Shelter

- Source of Heat

- Bleeding Control

- Navigation

- Communication

- Extra Water

- Extra Calories

- Extra Thermal Layers

- Sanitation

So let's get into it!

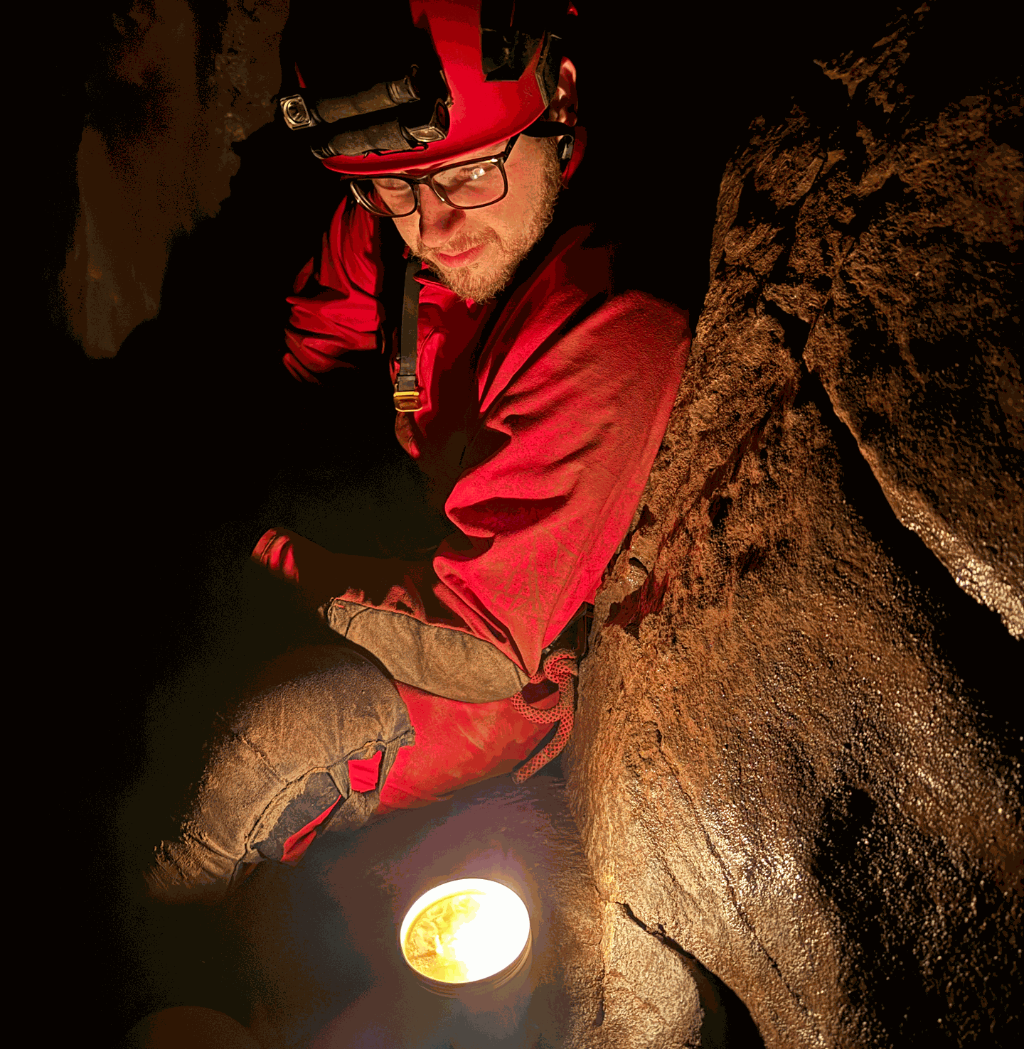

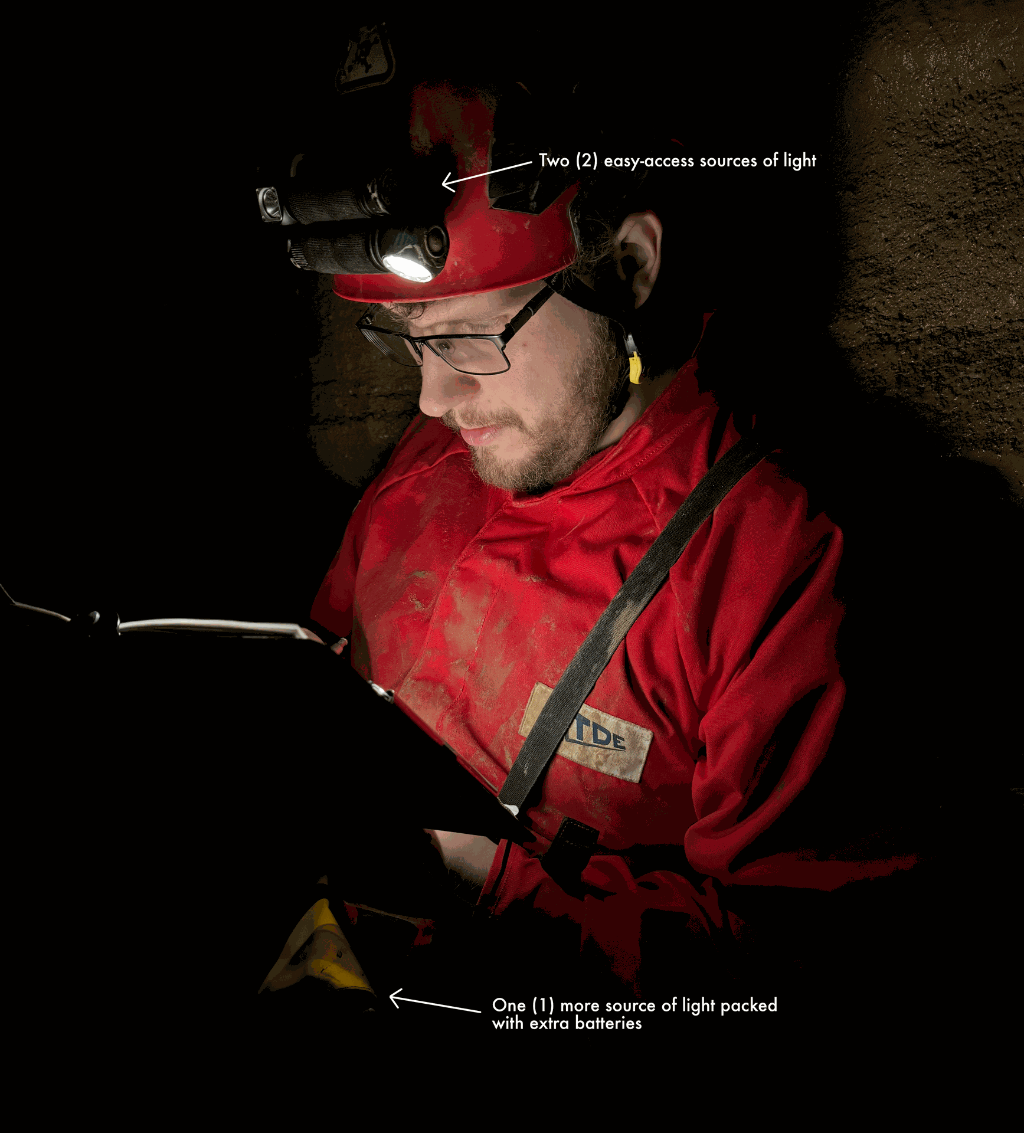

Backup Light/Batteries

Requiring light in cave is a given. Without light, you cannot safely move in cave. Cavers should already have two sources of light easily accessible (on their helmet), PLUS a third backup in your pack AND some extra batteries [2, p10]. All three (3) sources of light should be able to be worn as a headlamp (i.e. not require use of your hands in order to operate the light). You should think about the durability of your mounting system and plan for a backup solution for mounting your light if your primary mounting system fails. Loss of the ability to use your light as a headlamp isn't quite as bad as not having one, but it's not far behind when in a cave. A phone flashlight or a candle does not count as one of your three light sources, and we hesitate to call a handheld flashlight a light source either since it is not very useful for navigating in a wild cave.

Thermal Shelter

The Palmer furnace [3, p3-19] is our favorite must-have minimalist thermal shelter and is so easy to carry! For those who don't know, a Palmer furnace is a large trash bag worn similar to a poncho with a lit candle placed inside.

- TRASH BAG TIP: One of our tips is to use a 55-gal trash bag for most cavers. A contractor bag barely fit our 5'2" co-founder. Pack your trash bag in a durable waterproof bag to prevent it from getting muddy and torn up in the bottom of your pack. We like to vacuum-seal our trash bags, but a freezer ziplock would work okay too.

- CANDLE TIP: Make sure to pack a candle rated to last 6-12 hours. Paraffin wax tea lights are only good for 30-60 minutes, so you would need about 12 of them to hit the same duration as a survival candle and at that point space and weight dictate just carrying the survival candle. Beeswax is ideal because it will burn hotter for longer than most other types of wax.

- LIGHTING TIP: Don't forget that you'll need to be able to light the candle. Due to how critical this piece of gear is, we recommend redundancy just like we have with light sources. It's a good idea to carry at least three (3) options for lighting your candle. We like to carry two (2) different types as well. This might look like one BIC lighter and two stormproof matches (with striker), or two BIC lighters and a stormproof match (with striker).

A thermal bivvy [4] for long expeditions is a good idea too. Emergency blankets are reasonably effective if used properly but can be quickly damaged in the cave environment [3, p12-13]. However, emergency blankets are also lightweight multitaskers [5] that pack small so carrying one in addition to a Palmer furnace may be desirable. Thermal shelters should be made of a durable, waterproof material and be cheap to replace. Expensive shelter options aren't great, as you won't be motivated to use them until after hypothermia has already begun to set in. This is why we like the Palmer furnace as frontline defense for cave hypothermia - trash bags are cheap, durable, waterproof, versatile, and don't take up much space.

Source of Heat

Getting into a thermal shelter is the first step for a hypothermic patient but isn’t sufficient to re-warm an already cold patient. You need the ability to add heat to the thermal shelter faster than that heat is transferred to the cool cave air [3, p12-19]. Carrying a source of fire alone isn't enough, not to mention burning a campfire in cave isn't the best idea. Hypothermia is eventually a given in a cave environment - be prepared for it with at minimum a long-burning candle and a way to light it, as we discussed above with Palmer furnaces [6].

Jennifer also typically carries rechargeable hand warmers in addition to a candle to catch cold stress on the front end. The Zippo version gets caked with mud and stops working after a few trips, so we are currently in the testing phase with a new company (Ocoopa) to see if their hand warmers have better resilience in cave. "Hot Hands" and similar products are not advisable. They work based on oxidation, which happens extremely quickly in wet conditions. Wet Hot Hands will be very, very warm for a very, very short amount of time. Hot Hands also need oxygen to function, so they will stop working if tucked inside a tight pocket or packed into a tight hypothermia wrap.

For longer trips, hexamine-tab-fueled emergency stoves and a metal mug [7] let you have hot beverages to quickly rewarm a cold caver, which can be very effective in staving off hypothermia.

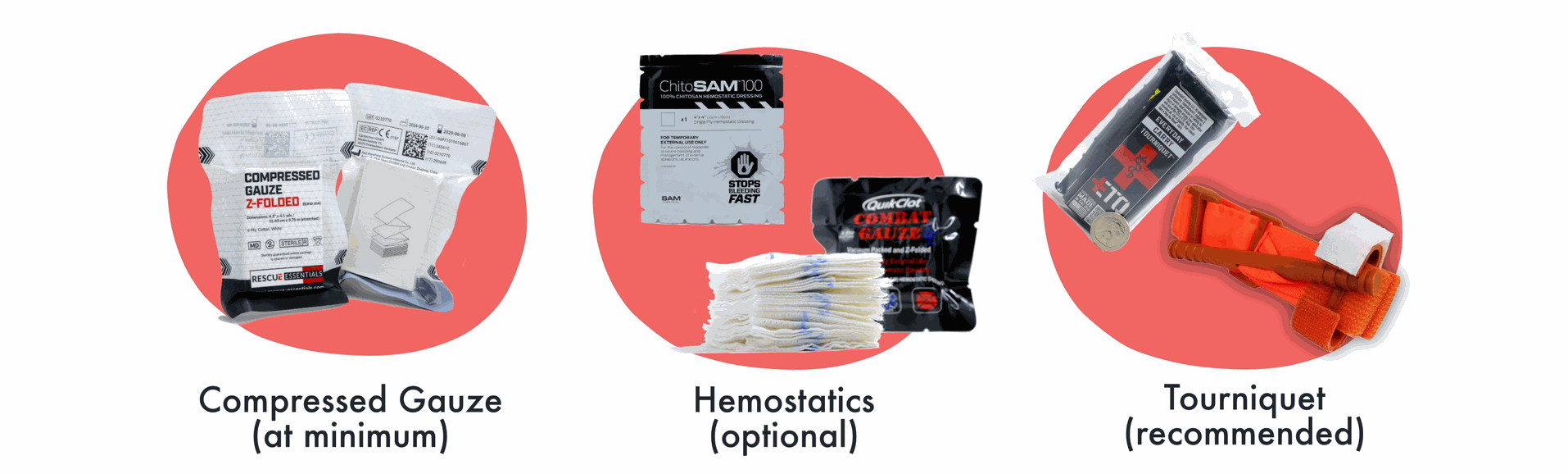

Bleeding Control

There is no substitute for bleeding control when you need it. At minimum, carry compressed gauze. Hemostatics such as QuikClot or chitosan-based products are a great option but are less versatile [8]. We also strongly recommend carrying a compact tourniquet [9]. When seconds count, you don't have time to try to improvise a semi-effective tourniquet out of your gear [10,11]. Other first aid gear is great to bring (in fact we strongly recommend it) but we consider bleeding control to be the top essential in a kit.

Navigation

A small roll of flagging and a mini compass can keep you oriented and prevent you from going in circles in a maze-like cave. If a map exists, print it out on waterproof paper and bring it with you. Getting lost is luckily uncommon for experienced cavers, but a quick review of American Caving Accidents indicates that it is a very real possibility. Also, don’t forget the approach hike! A long, difficult approach may necessitate carrying a GPS unit, topographic maps, or other navigational aids.

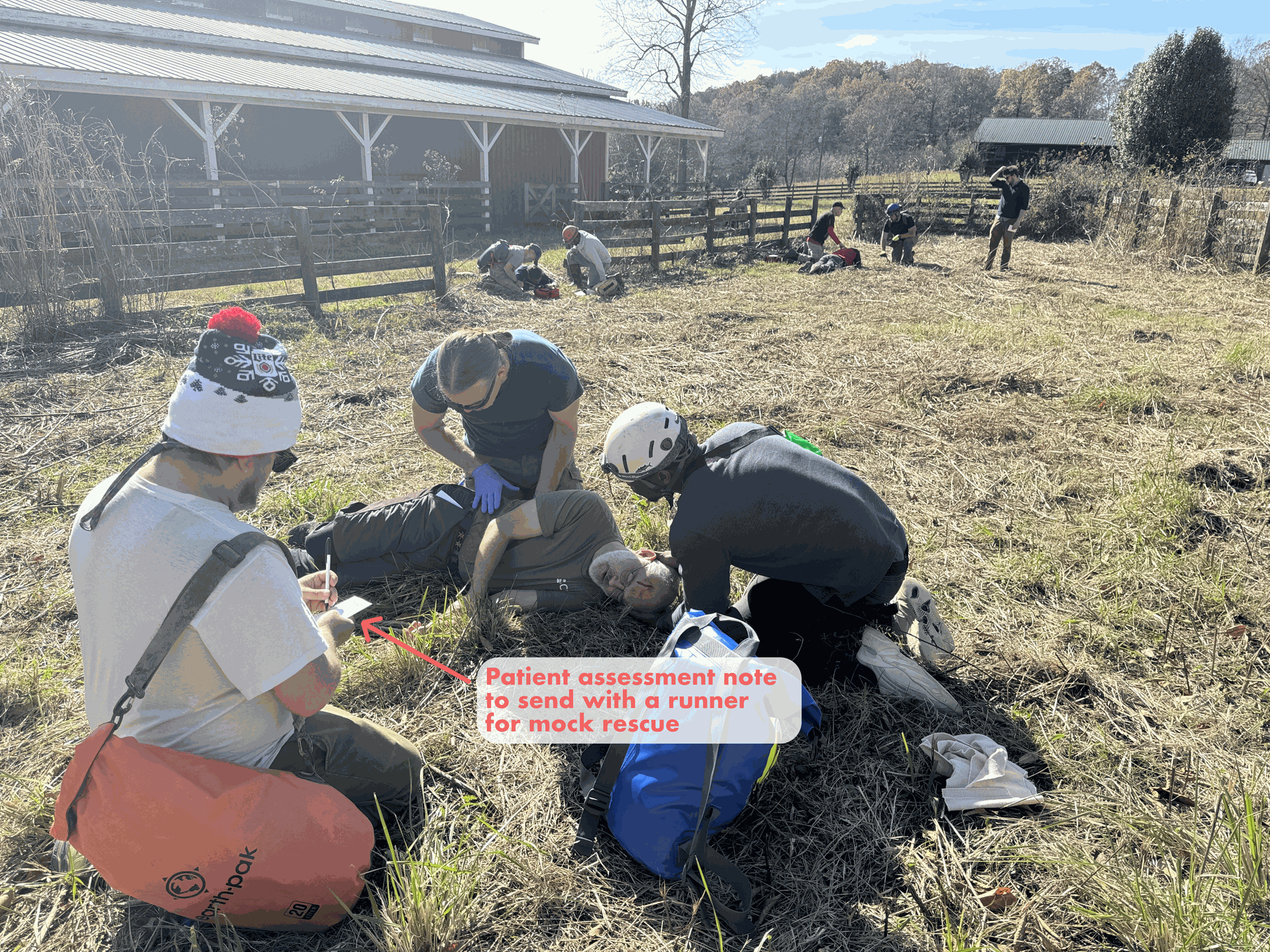

Communication

The ability to pass written notes lets you communicate with a split-up group or send information with a runner for a callout rescue [3, p4-8]. Flagging can be used to pass short messages, indicate direction of travel, or highlight the location of a note placed where other cavers may find it. If you are unable to move a patient from a side passage back to the “trade route,” flagging can help rescue personnel locate the group more quickly. Radios are of questionable efficacy in cave but can be very useful for large pits and communication between groups on the surface. Personal beacons or satellite phones will not work in cave, but they will work on the surface in areas without cell service, which could shorten mobilization time for a rescue.

Extra Water

Carry extra to drink and/or the ability to purify in place. Purifying bottles are great and lightweight for longer trips, since in wet caves you can carry less and plan to purify what you are going to use. However, most of these bottles are unable to filter out viruses - although they are effective at removing dirt, bacteria, and cysts [12]. For effective disinfection, chemically-treat filtered water prior to use [13]. It is strongly recommended that your base water consumption be stored in durable, hard-sided containers, like Nalgenes, to prevent the cave from damaging the container to the point of leakage.

A minimum of one liter of water should be carried for a short trip, but 2-3 liters are recommended for a full day or perhaps four (4) liters for a physically intensive trip or a trip with a long, hot approach hike. For a trip with a difficult approach you can consider stashing extra water on the surface for the hike back. It is worth noting again that this guideline is for the southeast. For any desert travel, three (3) liters is the minimum amount of water that should be carried for any length of trip and 4-5 liters is recommended for a physically demanding full day.

Extra Calories

These are required to stay warm and active. Make sure you and your group have sufficient calories for the trip, plus an extra reserve [3, p2-11]. Your primary calories for the trip are recommended to be well-rounded through all three (3) macronutrients (protein, carbs, fat) for both short and long-term energy. We also like to carry quick calories, like sugary snacks or gels, for situations (difficult climb-out, rescue, etc) where a quick burst of energy may be necessary or for when well-rounded snacks are difficult to digest. It can be useful to carry some of your reserve in a form that you are unlikely to snack on (for example energy gels in a non-preferred flavor). Gels can also be useful by having electrolytes included, or caffeine. However, be wary of included caffeine for patients experiencing a medical issue.

Extra Thermal Layers

Either for you, your patient, or your cold group members. If everyone carries a single extra thermal layer, the whole group will be in a lot better place during a shelter-in-place situation. For cold caves, carry puffers or other thick insulation. For wet caves, consider storing your extra warm layers in a dry bag or darren drum so they are dry when you need them.

Sanitation

Carry a "wag bag", "ReStop", or similar sanitation kit [14] with ability to sanitize your hands afterward. On long trips, lack of sanitation can lead to unpleasant illnesses. Leave-no-trace aside, human waste left in a cave can be a hazard to you and other cavers. Pack it out [2, p14].

A couple of items from the original (classic) list, specifically sun protection and a knife, may still be important to carry but are not considered to be as essential underground as the items we have added here. Removing sun protection is fairly obvious. Its inclusion on the classic list is primarily for mountaineering and alpine travel but is less important in our wooded mountains here in TAG, where shelter from sun is easy to find.

The knife - this is contentious. We know several people that always carry one, but in general, their use in cave is fairly limited. A knife should be the last resort for rope emergencies, however, there is pretty clear benefit in carrying one in swift water, wet multidrop rappels, or other situations where you may have to choose between the risk of cutting the rope and the risk of drowning. Chris usually carries a small multitool with a knife blade, scissors, and some various small tools. A set of shears or other cutting implement with a blunt tip would also be useful in responding to severe trauma where clothing must be cut. Although in a backcountry or austere environment cutting clothes should be a last resort due to potential for environmental and evacuation concerns.

This list is not meant to be exhaustive - there are plenty of other items that are appropriate for your caving gear. At SEM, we believe in the concept of a "mission-specific loadout". Meaning that your necessary gear will depend on the trip and should be planned based on anticipated hazards and contingencies.

As always, if you need to stock up on any of these essentials, come shop at our store and help support our mission to make good wilderness first aid training and gear available to cavers.

What would you change about this list?

Drop us a comment at info@southeastexpeditionmed.com.

References

1. What Are The Ten Essentials? The Mountaineers. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.mountaineers.org/blog/what-are-the-ten-essentials

2. Cheryl Jones. A Guide to Responsible Caving. Published online 2016. https://caves.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Guide_to_Resp_Caving_2016.pdf

3. Cartaya E, Speaect R. SPAR: Expedition and Small Party Cave Rescue Techniques. First edition. Vertically Speaking LLC; 2019.

4. Thermal Blanket - SOL Sport Utility Blanket. Southeast Expedition Medical. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.southeastexpeditionmed.com/shop/thermal-blanket-sol-sport-utility-blanket-280

5. Wallner B, Salchner H, Isser M, Schachner T, Wiedermann FJ, Lederer W. Rescue Blankets as Multifunctional Rescue Equipment in Alpine and Wilderness Emergencies—A Narrative Review and Clinical Implications. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(19):12721. doi:10.3390/ijerph191912721

6. Speleocandle | Southeast Expedition Med. Southeast Expedition Medical. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.southeastexpeditionmed.com/shop/speleocandle-222

7. Emergency Hot Beverage Kit. Southeast Expedition Medical. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.southeastexpeditionmed.com/shop/emergency-hot-beverage-kit-289

8. Littlejohn L, Bennett BL, Drew B. Application of Current Hemorrhage Control Techniques for Backcountry Care: Part Two, Hemostatic Dressings and Other Adjuncts. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26(2):246-254. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2014.08.018

9. Drew B, Bennett BL, Littlejohn L. Application of Current Hemorrhage Control Techniques for Backcountry Care: Part One, Tourniquets and Hemorrhage Control Adjuncts. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26(2):236-245. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2014.08.016

10. Walters TJ, Wenke JC, Kauvar DS, McManus JG, Holcomb JB, Baer DG. Effectiveness of Self-Applied Tourniquets in Human Volunteers. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005;9(4):416-422. doi:10.1080/10903120500255123

11. Cornelissen MP, Brandwijk A, Schoonmade L, Giannakopoulos G, Van Oostendorp S, Geeraedts L. The safety and efficacy of improvised tourniquets in life-threatening hemorrhage: a systematic review. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2020;46(3):531-538. doi:10.1007/s00068-019-01202-5

12. Backer HD, Derlet RW, Hill VR. Wilderness Medical Society Clinical Practice Guidelines on Water Treatment for Wilderness, International Travel, and Austere Situations: 2024 Update. Wilderness Environ Med. 2024;35(1_suppl):45S-66S. doi:10.1177/10806032231218722

13. CDC. About Water Treatment Options When Hiking, Camping, or Traveling. Drinking Water. September 4, 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/drinking-water/prevention/water-treatment-hiking-camping-traveling.html

14. Oh SH!T Kit | Southeast Expedition Med. Southeast Expedition Medical. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.southeastexpeditionmed.com/shop/oh-sh-t-kit-211